Digital Doomsday is coming and we should prepare for it

Modern Internet is not a pleasant place. Every page you visit greets you with annoying notifications and invisible hosts of trackers that avidly watch your every move, including mouse movements. To use it you need an enormously huge piece of software called «browser» that is now bigger than most operating systems, it's basically unmanageable and there's probably only a dozen people on the planet who fully understand how it works from top to bottom.

Not only that, most of the Internet now is just an app on your smartphone. You can't control it, you can't do anything about it.

The Internet becomes insanely complicated and unpredictable place.

In this post I try to outline some of my thoughts about a state of Digital Doomsday, why it could happen and what should we do about it.

What is a Digital Doomsday?

Digital Doomsday is a state when the Internet is no more. There could be different scenarios why we can lose the Internet (or access to the Internet). Let's review some of them starting with the least plausible.

- Don't Look Up!

Imagine huge asteroid falling on Earth and bringing death and destruction. Big enough rocks destroy almost all life on Earth quite regularly (in a geological perspective, of course). Although we usually think it's quite unlikely that a big rock size of Manhattan shall fall on Earth in the next Tuesday.

- How We Got Along After the Bomb

Not an impossible scenario, not at all! Right now Doomsday Clock shows 89 seconds to midnight. FYI, only 10 years age we were 3 minutes from midnight. If you watch news at least once a month you can see an ominous pattern: not a lot of peacemaking, quite a lot of warmongering.

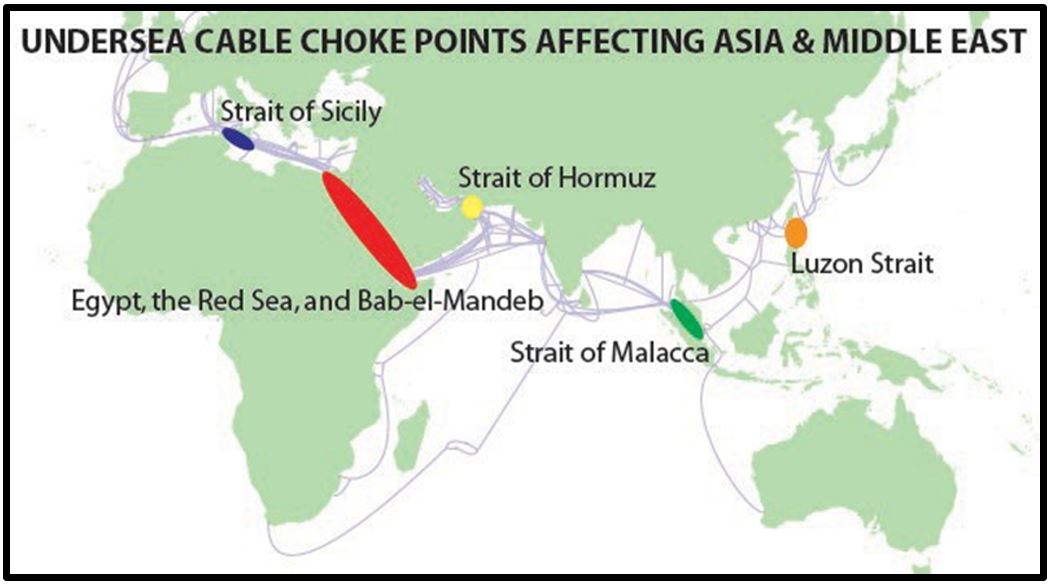

- Sabotage of submarine communication cables

Optic cables that lie on a seabed are extremely vulnerable. Just look at this map of SCC's choke points:

They are vulnerable.

Modern Internet is too centralized, too dependent on CDNs to survive a large scale attack on SCCs done right. There are no good guys in this game: any country or major geopolitical force is capable of doing that.

How possible is this? I have no idea. But looking at the last ten years, there's been a lot of things I had no idea about, and lo! they happen like the most obvious thing and nobody cares.

- Toxic Internet

All of the above scenarios, plausible or not, presuppose that you wouldn't be able to use the Internet, because it is no more (on a more or less global scale). But what if you wouldn't WANT to use the Internet? What if the Internet would be too hostile or too dangerous a place? In other words, the Internet may become toxic.

Toxic Interwastelands

Do you remember «The Right to Read» by Richard Stallman? It doesn't matter what you think about him personally, this story is brilliant. It was published in 1997 and having read it circa 2004 I thought to myself: «Ok, it was funny, but barely plausible». Little did I know back then. Little do I know now.

Nowadays the right to read is being slowly revoked. If you use modern Amazon Kindle for some reason, you don't own your ebooks anymore — you only license them. Also, publishers can modify and censor the books you thought you own following some current cultural and political agenda.

The Internet is just four sites, and they're not even sites anymore, they're generally an apps on your phone. These apps are a walled gardens, you can't even access public info posted there if you have no account (why don't you? It's free and it only takes a minute!)

All-pervasive AI follows you everywhere trying to replace you in your everyday tasks (and failing miserably).

In UK you can't even watch porn without confirming your real identity (if it isn't a reason enough to stop watching porn, what is?) Other countries watch how it goes with sincere interest, no doubt. European age verification app might actually ban any Android phone not licensed by Google.

Microsoft designed a Pluton to further «enhance security» by storing your encryption keys and other sensitive data in a black box implemented right inside your CPU. It's for your own good, obviously (actually, it's not the first time they're doing something like this, they have already tried the same trick back in 2002 with Microsoft Palladium, but then they failed).

And while we're at it, good ol' Microsoft also screenshots everything you do on your computer and sends it somewhere on the Internet, including passwords and credit card data.

In many countries you HAVE TO own and use a smartphone to actually exist and use public and governmental services. In my country most banks don't even have any web interface whatsoever — only an app that just wouldn't work on your jailbroken Android device.

This is what we have NOW. It's not a dystopia, not a Stallman's fantasy from almost 30 years ago, not a spooky doom-and-gloom fib, it's a reality. And we obviously ask ourselves what will happen tomorrow?

Honestly, I have no idea. But there is a chance that at some point you might realize that you just can't use the Internet anymore because everything you have is several apps filled with mindless and mind-numbing «funny» videos while everything else is forbidden. Net neutrality is already shaky as hell. Sooner or later your Internet may become a feudal landscape, only with TikTok and fast pizza delivery services.

May be at some point you'd think you had enough.

Are there any silver linings?

Of course, there are.

Right now we have a lot of open-source OSes, we have sane initiatives to lessen the dependency on huge tech companies with proprietary tools, we have Fediverse, we even have local and open-source AI.

Things look bright, don't they?

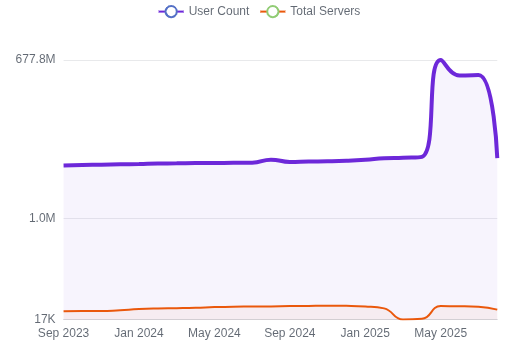

Fediverse stats aren't promising, to be honest...

No matter how bright are the skies, we still need plan B.

We need to develop and invent new ways to bring people together (be it Fediverse or some obscure privacy-first mesh networks). But we also need to figure out how to survive on our own and grow our own vegetables (figuratively and literally).

Which means we have to plan our digital prepping.

As I see the problem, we need the data to survive (and quite possibly to rebuild the civilization) and tools for general computing.

What about the data?

Books, articles, knowledge bases, you name it. There are great projects that can help you to build your own «offline data center», like Kiwix.

With Kiwix you can download the whole Wikipedia (and not only that) to your device. Kiwix works pretty much on any OS and works fine.

We also need physical books for redundancy and ease of use (and physical media in general — for example, movies on DVD and BluRay, and music on CDs).

I'd recommend to check out thrift book stores close to you or on eBay. There are also places like Abebooks where you can buy precious books like «Programming Perl» or «Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment» for a couple of bucks.

What about the tools?

We need a serious and reliable OS on our lonely journey, so it won't be Windows or MacOS, obviously. Back in the days Windows would be number one choice because it worked everywhere, had a huge software library and supported everything you can throw at it. But now even Windows 10 won't work properly without an SSD, not to mention RAM and CPU requirements. And actually modern Windows is more like a surveillance machine with extra features like Notepad and Calculator. So Windows is out of the question.

Let's try to outline some criteria for our OS (and software) of choice.

- It should be open-source.

- It should be easy to maintain.

- It should be possible to work on its source code (because there probably wouldn't be anyone to do that except yourself).

- It should have low system requirements and support most of the hardware.

- It should have a lot of software available.

- It should have a good documentation (and/or porter's and developer's guides).

So that kinda narrows it down a bit. Basically we have to exclude all rolling Linux distros, overbloated distros and stick with LTS releases.

Below are some of OSes that I'd choose. It's not an ideal and only choice you should have. It's just what I would choose. For example, there are BSDs like NetBSD or DragonflyBSD that I didn't put on the list because I just don't know enough about them.

Slackware has a great reputation as one of the oldest maintained distros out there (actually, one of the oldest distros ever). It comes with a huge variety of software out of the box and even has 32-bit version (as of version 15.0).

Slackware uses simple init system based on rc-files and generally sticks to the KISS principle and «user knows better». It always does what it's told and doesn't try to overrule or restrain you.

Out of all Linux distributions Slackware is considered the most BSD-like.

Generally, even on an island in an ocean Slackware is more than enough to get you started: it comes with all the software you might need. One of the important Slackware «features» is the fact that there's no dev-packages. Every software package comes with all required development libraries, headers and docs, so it's very easy to compile new software for Slackware: you probably already have all the dependencies.

And while we're at it, Slackware doesn't do dependency checking, but there are a lot of community tools like sbotools that can do that for you.

Debian doesn't require any special introduction: it's a very old distribution that values security and stability. In some areas it might even be considered «a vanilla Linux», because it's so popular, simple and heavily documented.

One of the selling points of Debian has always been a huge number of software packages available.

Sadly, in recent years Debian does not provide ready DVD/CD images for this software, you have to build them yourself using a jigdo utility, but that's hardly a problem when you prepare for a harder times.

Most importantly, you can build «source» images that contain all the necessary source code.

FreeBSD has so many advantages that I'll just outline them briefly and leave a link to a great article by the famous vermaden «Quare FreeBSD»: complete system (unlike Linux which is just a kernel plus a bunch of packages), simplicity, documentation, init system and, most importantly in our case: ZFS.

ZFS is a survival grade file system that does everything you might need from a file system: self-healing, snapshots, reliability, sending/receiving datasets over the network, even Boot Environments (basically, it makes really hard to kill a FreeBSD). ZFS is a first-class file system in FreeBSD, unlike Linux that has incompatible license and doesn't have some great ZFS features like Boot Environments (also, doing ZFS-on-root is still a huge lottery on Linux).

And in a situation like Digital Doomsday you REALLY need a good file system.

I love OpenBSD for its extreme simplicity and straightforwardness.

I don't know how they do it every time, but OpenBSD developers somehow manage to solve problems as they are instead of creating a whole lot of abstractions and generalized solutions: if you need to connect to Wi-Fi, you just do ifconfig; if you need to mount a drive, you do just that.

OpenBSD is a secure and robust operating system that comes as a whole package. The only serious downside of OpenBSD (for me) is lack of a good file system.

FFS2 is a «good-enough» file system, but don't raise your hopes: it works, but it doesn't come even close to ZFS in any respect.

Solène Rapenne in her article «What if Internet stops? How to rebuild an offline federated infrastructure using OpenBSD» brings up some good points why OpenBSD might be an OS of choice to rebuild the Internet.

It's pretty easy to organize your local repository for OpenBSD. For example, all of the amd64 packages for OpenBSD 7.7 take only ~80 Gb in size, so its quite manageable. But, as Solène mentions, OpenBSD ports distfiles is what we really need.

So, if we try to assert how many disk space we need for all ports on OpenBSD 7.7, we'll get this picture:

me@desktop:~/ports$ find . -name "distinfo" -type f -exec grep "SIZE" {} \; | sort -u | awk '{total+=$4}; END {print total}'

118157658347

If my unix-fu isn't terribly wrong, it means around 118 Gb. Again, not that much, and we'll have all the source code we could possibly need along with OpenBSD-specific patches.

Some concluding thoughts

Some people might say that it's a some kind of defeatism and we should rally up and fight for our digital freedom instead. That might or might not be true: not everyone is inclined to activism in any shape or form.

But anyway I think that having a last line of defense in form of just your personal computer that is capable to function fully autonomously is a necessary step. Because if you don't have this last line of defense already prepared, what will you do when all other lines would fall?

Self-hosting was just a phase one.

Prepare for Digital Doomsday, for it is nigh.